Converting floating-point numbers to their shortest decimal representations has long been a surprisingly challenging problem. For decades, developers relied on algorithms such as Dragon4 that used multi-precision arithmetic. More recently, a new generation of provably correct and high-performance algorithms emerged, including Ryu, Schubfach and Dragonbox.

In my earlier post, double to string conversion in 150 lines of code, I explored how compact a basic

implementation can be while still maintaining correctness. The Schubfach

algorithm pushes this idea much further: it enables fully proven,

high-performance dtoa with an amount of code comparable to the naïve

algorithm. This post gives a brief overview of Schubfach and then walks through

the minimal C++ implementation in https://github.com/vitaut/schubfach.

A brief overview of the Schubfach algorithm

The Schubfach algorithm, introduced by Raffaello Giulietti, is a method to convert binary floating-point numbers into the shortest, correctly rounded decimal string representation with a round-trip guarantee. It is based on two key insights:

1. The non-iterative search guided by the pigeonhole principle

The algorithm is founded on the Schubfachprinzip (the pigeonhole principle), which gives the algorithm its name, to efficiently determine the correct decimal exponent ($k$) for the optimal shortest decimal representation ($d_v$).

Instead of iteratively searching for the shortest decimal representation, Schubfach determines a unique integer exponent $k$ based on comparing the distance between adjacent decimal values ($10^k$) in a given scale ($10_k$) against the width of the floating-point number’s rounding interval ($\Vert R_v \Vert$).

The exponent $k$ is calculated such that $10^k \leq \Vert R_v \Vert < 10^{k+1}$. This comparison guarantees that the set of decimals rounding back to the original floating-point value $v$ ($R_k$) contains at least one element, and the set at the next finest resolution ($R_{k+1}$) contains at most one element.

This approach makes the algorithm non-iterative.

2. Guaranteed accuracy through fixed-precision integer estimates

Schubfach achieves high performance by replacing costly, arbitrary-precision

arithmetic (like BigInteger in Java) with reduced, fixed-precision integer

arithmetic.

This shift to efficient fixed-precision computation is made possible and guaranteed correct by the Nadezhin result.

This result establishes that critical scaled boundaries of the rounding interval are never extremely close to an integer. Specifically, there is a $2\varepsilon$-wide zone around integers where these boundaries cannot exist, except when they are exactly an integer.

This separation allows the algorithm to safely use limited precision overestimates derived from precomputed tables of powers of 10. These estimates are close enough to the true values that they produce the exact same rounding decision as the full-precision values.

Rounding Interval

A floating point number $v = c 2^q$ represents not just a single real value but an entire rounding interval $R_v$ that contains all real numbers that round back to $v$. For a finite positive value, the interval is bounded by $v_l = c_l 2^q$ and $v_r = c_r 2^q$, where $c_l$ and $c_r$ are midpoints between $v$ and its predecessor and successor. In the common case of regular IEEE 754 spacing, these are $c_l = c − 1/2$ and $c_r = c + 1/2$. In the rare irregular case near powers of two, the left midpoint becomes $c_l = c − 1/4$. The width of the interval is $\Vert R_v \Vert = v_r − v_l$, and every real number strictly between the endpoints will round to $v$. The rounding mode determines whether the endpoints themselves are included. For example, with round-to-even, both endpoints belong to $R_v$ when $c$ is even and both are excluded when $c$ is odd.

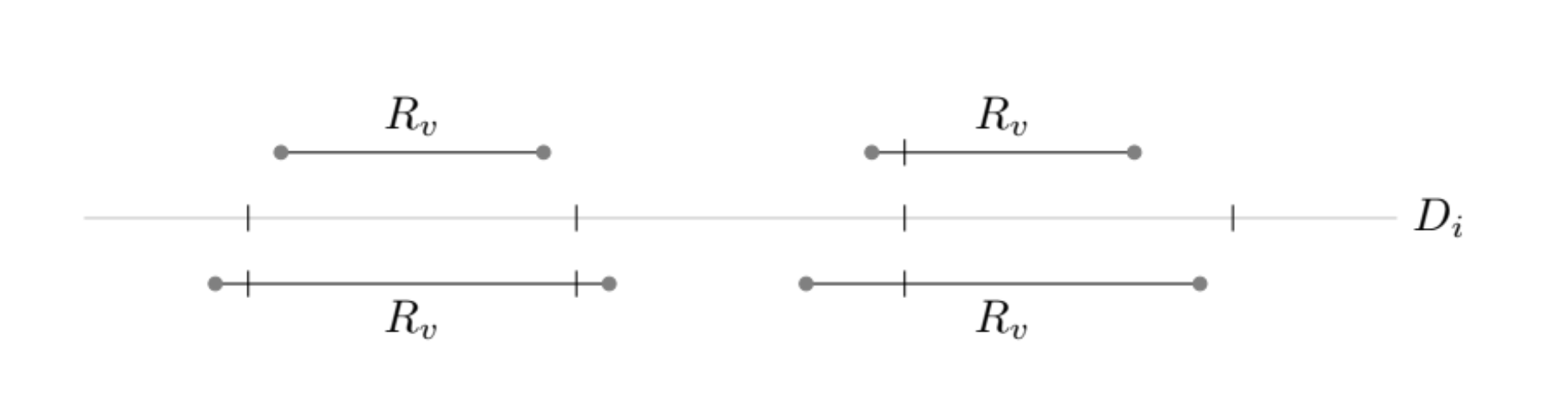

Formatting a floating point value does not require reproducing its full decimal expansion. Any decimal inside $R_v$ is guaranteed to round back to $v$, so the goal is to choose the shortest such decimal (in terms of the number of decimal digits in the significand). Schubfach does this by examining how $R_v$ intersects decimal grids ($D_i$) of various scales. If the spacing $10^i$ is narrower than the width of $R_v$, then at least one decimal of that scale must fall within the interval. If the spacing is wider, at most one can. By finding the exact scale where this transition occurs, the algorithm pinpoints the minimal length at which candidates exist.

The following figure illustrates this principle visually. It shows several evenly spaced tick marks representing values in a chosen decimal grid $D_i$, while the rounding intervals $R_v$ are drawn as horizontal segments. When the grid spacing is too coarse, the ticks may all fall outside the interval, meaning no decimal of that length can represent $v$. When the spacing is too fine, multiple ticks fall inside, meaning several decimals of that length round to $v$. Schubfach identifies precisely the grid levels where the interval captures at least one and at most one such tick, allowing it to choose the shortest decimal that is still unambiguous during round-trip conversion.

Figure from “The Schubfach way to render doubles” by Raffaello Giulietti, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Minimal C++ implementation of Schubfach

Now let’s look at the implementation from https://github.com/vitaut/schubfach.

1. Extract IEEE-754 fields

To begin the conversion, we first extract the IEEE-754 components: the sign

bit, the exponent field (bin_exp), and the 52-bit significand (bin_sig).

Using std::bit_cast, we interpret the

floating-point value as an unsigned integer and use bit manipulation to extract

the components:

uint64_t bits = std::bit_cast<uint64_t>(value);

constexpr int precision = 52;

constexpr int exp_mask = 0x7ff;

int bin_exp = static_cast<int>(bits >> precision) & exp_mask;

constexpr uint64_t implicit_bit = uint64_t(1) << precision;

uint64_t bin_sig = bits & (implicit_bit - 1); // binary significand

We output the sign right away and handle special cases such as ±infinity, NaN and zero, writing them out and returning early:

if (bin_exp == exp_mask) {

memcpy(buffer, bin_sig == 0 ? "inf" : "nan", 4);

return;

}

2. Normalize representation

The next step is to normalize the representation by adding an implicit bit if necessary and adjusting the exponent:

bool regular = bin_sig != 0;

if (bin_exp != 0) {

bin_sig |= implicit_bit;

} else {

++bin_exp; // Adjust the exponent for subnormals.

regular = true;

}

bin_exp -= precision + 1023; // Remove the exponent bias.

Now the absolute value of the original number is equal to

bin_sig * pow(2, bin_exp).

We also determine if the rounding interval is regular (symmetric). Irregularity occurs when the spacing between adjacent FP numbers increases, which happens for numbers that are powers of 2 and not subnormal.

3. Shift the significand

To make the boundaries of the rounding interval integers we shift the significand left by two:

uint64_t bin_sig_shifted = bin_sig << 2;

and set the boundaries:

uint64_t lower = bin_sig_shifted - (regular ? 2 : 1);

uint64_t upper = bin_sig_shifted + 2;

4. Compute the decimal exponent and power of 10

We compute the decimal exponent (dec_exp or $k$ in the paper) as

floor(log10(pow(2, bin_exp))) using fixed-point arithmetic:

int dec_exp = regular ? floor_log10_pow2(bin_exp) : /* … */;

where floor_log10_pow2 is defined as

// floor(log10(2) * 2**fixed_precision)

constexpr long long floor_log10_2_fixed = 661'971'961'083;

constexpr int fixed_precision = 41;

// Computes floor(log10(pow(2, e))) for e <= 5456721.

auto floor_log10_pow2(int e) noexcept -> int {

return e * floor_log10_2_fixed >> fixed_precision;

}

For irregular intervals, an additional adjustment for log10(3/4) is included.

The decimal exponent (or, rather, its negation) is then used to look up the

126-bit significand of an overestimate of a power of 10 from a table,

precomputed with a Python script, gen-pow10.py. Those are returned

as two uint64_t numbers, pow10_hi and pow10_lo, becaue C++ doesn’t

have standard 128-bit integers.

An interesting artifact of the table is that it stores values as pairs of 63-bit integers, likely because the algorithm was targeting Java which lacks unsigned integers. This is kept for now to keep the implementation close to the reference but can potentially be simplified in the future.

5. Scale by power of 10

The next step is to multiply the significand and boundaries by the power of 10 we obtained earlier:

uint64_t scaled_sig =

umul192_upper64_modified(pow10_hi, pow10_lo, bin_sig_shifted << shift);

lower = umul192_upper64_modified(pow10_hi, pow10_lo, lower << shift);

upper = umul192_upper64_modified(pow10_hi, pow10_lo, upper << shift);

This is probably the most complicated part of the whole algorithm. It relies

on special (modified) rounding to make sure that the later comparisons of the

integer candidates with the bounds give the same results as those we would

get with full precision (using rationals or bigints). There is also a small,

obscure shift applied to bring the intermediate result in

umul192_upper64_modified in the required range. Going into details here is

out of scope of this post but if you are interested check out sections 9.5 and

9.6 of the paper.

6. Select the candidate

Now that we have our scaled value and boundaries, we can construct and select from up to four candidates:

- Two corresponding to

dec_exp + 1($k + 1$), from which at most one can fall into the rounding interval:- Underestimate with significand

dec_sig_under2 - Overestimate with significand

dec_sig_over2

- Underestimate with significand

- Two corresponding to

dec_exp($k$) with at least one belonging to the interval:- Underestimate with significand

dec_sig_under($s$) - Overestimate with significand

dec_sig_over($t$)

- Underestimate with significand

The checks are very similar so let’s consider the smaller decimal exponent

(dec_exp) case. We determine whether the underestimate is in the interval

(under_in) by comparing it against the lower boundary taking into account

the least significant bit of the binary significand for rounding and similarly

for the overestimate:

uint64_t dec_sig_under = scaled_sig >> 2;

uint64_t dec_sig_over = dec_sig_under + 1;

uint64_t bin_sig_lsb = bin_sig & 1;

bool under_in = lower + bin_sig_lsb <= dec_sig_under << 2;

bool over_in = (dec_sig_over << 2) + bin_sig_lsb <= upper;

if (under_in != over_in) {

// Only one of dec_sig_under or dec_sig_over are in the rounding interval.

return write(buffer, under_in ? dec_sig_under : dec_sig_over, dec_exp);

}

If both are in the interval then we select the closest:

int cmp = scaled_sig - ((dec_sig_under + dec_sig_over) << 1);

bool under_closer = cmp < 0 || cmp == 0 && (dec_sig_under & 1) == 0;

return write(buffer, under_closer ? dec_sig_under : dec_sig_over, dec_exp);

7. Write the output

Once the decimal significand is chosen we forward it together with the decimal

exponent (dec_exp) to the write function that writes the number into the

output in the exponential format. We all know how to format integers quickly.

Performance

The current implementation doesn’t apply all optimizations from Schubfach, just the ones replacing which wouldn’t bring much benefit in terms of simplicity or could potentially harm correctness. In particular, we skip the fast path from section 8.3 when $q < 0$ and $v \in \mathbb{Z}$. Hopefully, the implementation can still be legally called Schubfach despite those optimization budget cuts.

Let’s try to see how well this basic version of the algorithm performs on the dtoa-benchmark (https://github.com/fmtlib/dtoa-benchmark):

The performance is comparable to (or slightly better than) Ryu, ~70% worse than

Dragonbox and whopping 21 times better than sprintf. This is great for the

implementation which is only ~200 lines of code including comments and not

including generated tables.

Conclusion

I find it remarkable that a state-of-the-art algorithm for converting a double

to its shortest decimal representation can be implemented in just two hundred

lines of portable C++ code. The resulting implementation is relatively

straightforward if you’re familiar with common bit-fiddling techniques, with

the exception of the modified rounding step. This part is a subtle piece of

logic that I simply reproduced rather than fully internalized. Sometimes you

really do have to trust the math.

The performance is competitive with the best existing algorithms, and with a

few extensions such as __uint128_t it could be pushed even further.

I hope you find this useful. The complete code is available under a permissive MIT license at https://github.com/vitaut/schubfach.

Last modified on 2025-11-29